by William Ecenbarger

There’s a new epidemic across America–burnout among healthcare workers. Although the initial focus had been on physicians and nurses, a new study found the burnout problem impacting the entire healthcare workforce–pharmacists, social workers, respiratory therapists, hospital security officers, and staff members of health care and public health organizations.

There’s a new epidemic across America–burnout among healthcare workers. Although the initial focus had been on physicians and nurses, a new study found the burnout problem impacting the entire healthcare workforce–pharmacists, social workers, respiratory therapists, hospital security officers, and staff members of health care and public health organizations.

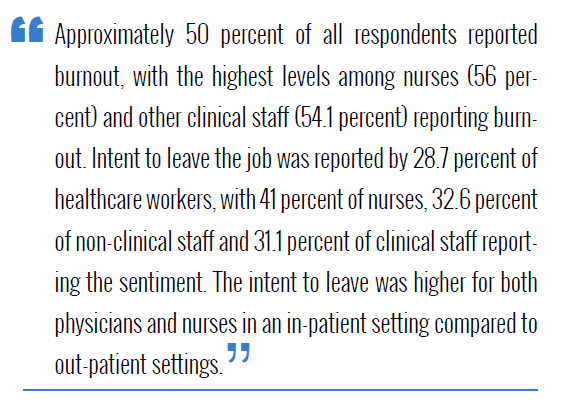

The results of a survey of more than 40,000 healthcare workers by the Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital was reported in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Health officials are nearly unanimous in stating that the burnout crisis will make it more difficult for patients to get needed care, cause an increase in health care costs, and exacerbate existing healthcare disparities. As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has launched an initiative that “puts the onus on management, not workers.”

“All too often, steps to ease the burnout health care workers seem to start and end with variations of the advice to ‘take care of yourself,’” the CDC said. “Instead, a new anti-burnout campaign from the CDC and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health turns to leaders of the workplace, not the workers, for solutions.”

The program, which is called “Impact Wellbeing,” aims to give hospital officials evidence-based resources to provide strategies to “reduce burnout, normalize help-seeking, and strengthen professional wellbeing.” Among the tools employed by the CDC are a questionnaire for workers to express their misgivings, workshops on topics like work-life balance, and “a guide encouraging leaders to share their own struggles with mental health to help encourage staff to do the same.”

Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy said the root cause of burnout can be traced to systems. “Causes include inadequate support, escalating workloads and administrative burdens, chronic under-investment in public health infrastructure, and moral injury from being unable to provide the care patients need. Burnout is not only about long hours. It’s about the fundamental disconnect between health workers and the mission to serve that motivates them.”

Forbes magazine reported last year that many troubled healthcare workers do not feel valued. “The fact that nearly 7 in 10 clinicians do not feel valued from the work they provide is nothing short of disturbing, and healthcare systems should work tirelessly to be strong advocates of their own employees,” the magazine said.

The Harvard study noted that burnout disproportionately impacts women and minority groups “due to pre-existing inequities around social determinants of health, exacerbated by the pandemic.”

Surgeon General Murthy outlined a five-step process of actions to deal with the problem

“Addressing health worker well-being requires first valuing and protecting health workers. That means ensuring that they receive a living wage, access to health insurance, and adequate sick leave. It also means health workers should never again go without adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) as they have during the pandemic. Furthermore, we need strict workplace policies to protect staff from violence: according to National Nurses United, 8 in 10 health workers report having been subjected to physical or verbal abuse during the pandemic.”

”We must reduce administrative burdens that stand between health workers and their patients and communities. One study found that in addition to spending 1 to 2 hours each night doing administrative work, outpatient physicians spend nearly 2 hours on the electronic health record and desk work during the day for every 1 hour spent with patients — a trend widely lamented by clinicians and patients alike.”

“We need to increase access to mental health care for health workers. Whether because of a lack of health insurance coverage, insurance networks with too few mental health care providers, or a lack of schedule flexibility for visits, health workers are having a hard time getting mental health care. Expanding the mental health workforce, strengthening the mental health parity laws directed at insurers, and utilizing virtual technology to bring mental health care to workers where they are and on their schedule are essential steps.”

“We need to increase access to mental health care for health workers. Whether because of a lack of health insurance coverage, insurance networks with too few mental health care providers, or a lack of schedule flexibility for visits, health workers are having a hard time getting mental health care. Expanding the mental health workforce, strengthening the mental health parity laws directed at insurers, and utilizing virtual technology to bring mental health care to workers where they are and on their schedule are essential steps.”

“We can strengthen public investments in the workforce and public health. Expanding public funding to train more clinicians and public health workers is critical. Increased funding to strengthen the health infrastructure of communities–from sustained support for local public health departments to greater focus on addressing social determinants of health such as housing and food insecurity–advances health equity and reduces the demands on our health care system.”

A feeling that millions of health workers, including me, have had during our careers. Culture change must start in our training institutions, where the seeds of well-being can be planted early. It also requires leadership by example in health systems and departments of public health. Licensing bodies must adopt an approach to burnout that doesn’t punish health workers for reporting mental health concerns or seeking help and that protects their privacy. Finally, many health workers still face undue bias and discrimination based on their race, gender, or disability. Building a culture of inclusion, equity, and respect is critical for workforce morale.”

“Today, we all have a role to play in preventing health worker burnout,” the CDC said. “Together, we have the capacity—and the responsibility—to provide our health workforce with all that they need to heal and to thrive.”